Thinking

Evolving at the pace of AI

We dedicated our summer retreat to exploring the intersection of design and AI. We spent two days discussing and experimenting with how our design process is changing and what skills are needed to support this transformation.

In mid-June, the entire Tangible team took time off for our summer company retreat. It’s a ritual that takes place twice a year, in summer and winter, to set aside time for meetings and to be present physically, mentally, and emotionally. These are moments we dedicate to ourselves, sometimes to learn, sometimes to share perspectives, and other times simply for the pleasure of being together. We always try to grow as a team.

This time, we devoted the retreat to asking questions. The central question was: How do we interpret the intersection between design and AI? How does it change the way we work or design things?

As we always do, we applied the same methods we use for our clients' projects to ourselves. We designed and facilitated workshops dedicated to exploring a different problem or question each time, combining techniques and tools specifically for the occasion.

Where are we now?

We are in a transitional moment, just before a transformative one.

Some compare this moment to the advent of photography in the mid-1800s. For some, painting was finished; for others, it was liberated from the burden of reproduction, free to express its full potential. Today, we remember Impressionism as one of the most fertile periods in art history.

In some ways, design is undergoing a similar shift, from a heavily industrialized execution tool to a practice of sense-making and the strategic exploration of problems and opportunities.

New articles, research, and papers on AI are published daily, and the rate of change surrounding AI is exponential. The proliferation of frameworks, approaches, adoption models, and more is also exponential. Keeping up demands a significant time investment and considerable cognitive effort.

However, some particularly interesting points emerged during our retreat from the models we’ve gathered and the experiments we’ve done in recent months that we want to share here.

New models

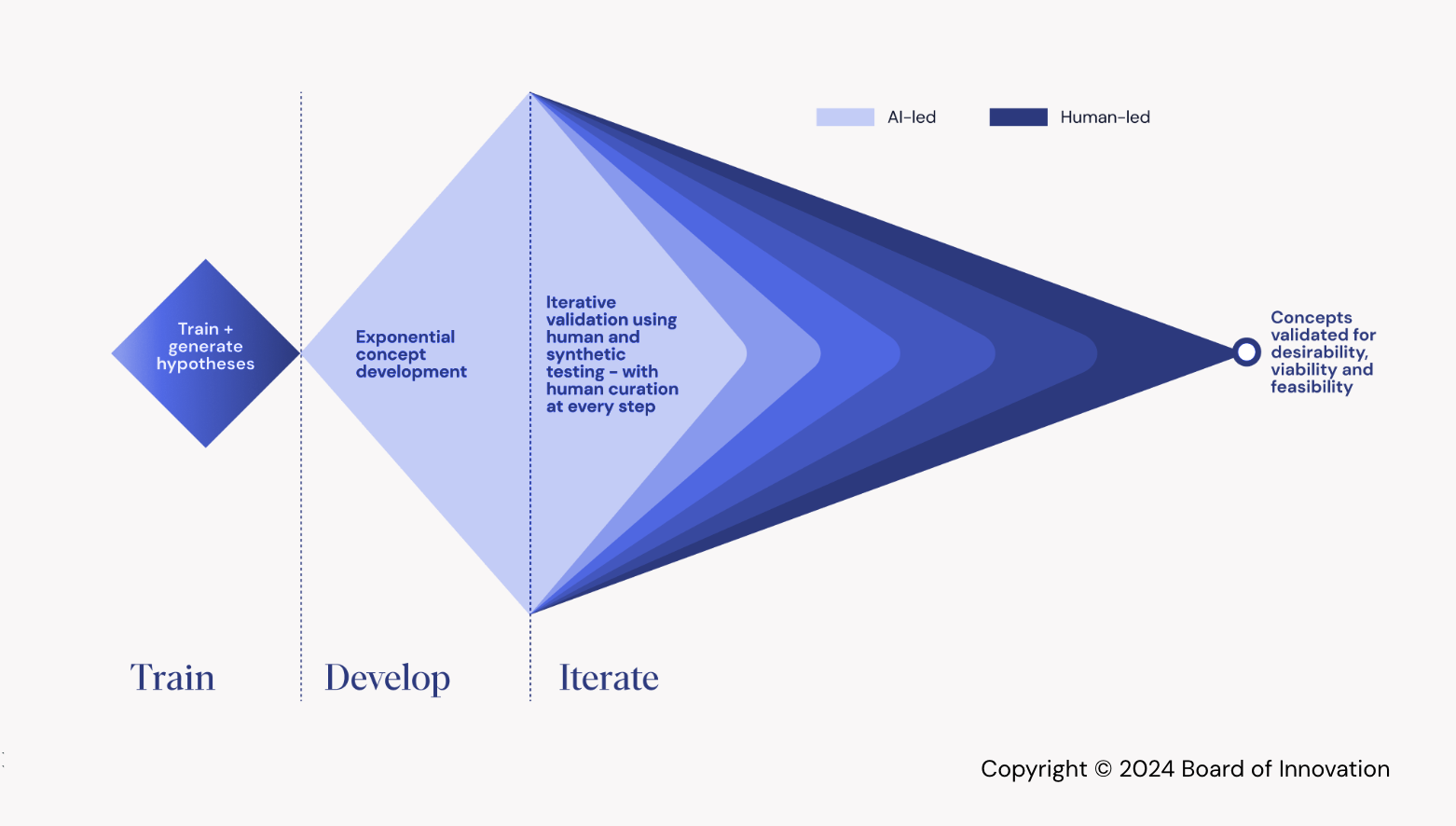

In short, the Stingray Model is an updated version of the well-known Double Diamond model. It highlights how AI opens new spaces in the divergent phase of the process, driving the time and cost of producing more ideas and concepts close to zero.

In the convergent phase, when choosing which path to take and deciding which solution best fits the problem, human judgment remains key. We are always in a context of amplification, not substitution.

At Tangible, we already use AI in exactly this way, as an additional teammate in the co-design and concept phase and to visualize ideas. We "make ideas tangible" in ever shorter times, which is one of the foundations of our brand.

It's not just about efficiency, but also effectiveness. We can broaden the range of choices, see an idea concretely before deciding, and compare based on a visual artifact rather than abstract concepts. We've always done this with concepts and prototypes, but with AI, this process is truly amplified.

Lean UX in a new light

About ten years ago, we invited Jeff Gothelf to Italy to lead a Lean UX workshop. We were thrilled by his approach, which has shaped our work ever since.

The process involves ideation, validation, prototyping, and development to gather evidence and iterate.

However, the dependencies on external teams and the complexity of projects often made these iterations lengthy, extending the time from idea to validation. Today, with a design team that combines hybrid skills and AI expertise, we can use Lovable, Bolt, or similar tools to move from idea to working prototype in days, if not hours.

There’s a crucial caveat here: Speed itself is not a value. The same goes for clients and stakeholders. Jumping to solutions, hypnotized by the power of AI tools and execution speed, doesn’t solve design debt; it amplifies it. What’s needed is a deep understanding of the problem connected to business and user benefits, with clear success metrics.

Otherwise, we risk producing many quick solutions to problems that don't exist, have little value, or, worse, are framed incorrectly.

Lowering the cost and time of prototyping is valuable for exploring more ideas, visualizing them, and making better decisions about which solutions are appropriate and effective for the identified problem or opportunity. In this sense, AI is a powerful amplifier that removes constraints.

If "good" is all that remains after fast and cheap come easy, then what does "good" mean right now?

Insight, strategy, originality, taste, experience—those are the things that remain scarce in an era where fast and cheap are abundant. The opportunity is to focus less on grinding out efficiencies and more on creating value through new (and newly possible) experiences.

-Josh Clark

Josh Clark - Source: LinkedIn

The roles and skills of tomorrow today

But speed isn’t only about prototypes. It raises deeper questions, too: Who will be responsible for designing these scenarios, and what tools will they use? That’s where our reflection on the roles and skills of the future began.

Through a workshop and a futures cone, we imagined the innovation projects and challenges that our clients will face in the coming years. Then, we worked backwards to determine what design teams and skills will be needed to address those scenarios.

This process led us to fundamental questions. For example:

- In highly complex scenarios, systemic skills are most useful: Service design, research, and business design. Are these skills becoming the new consulting? Perhaps it's not about providing advice and predictions, but rather, facilitating the emergence of collective knowledge and thinking?

- If interfaces become dialogues or dissolve into voice or spatial interactions, what are we talking about when we talk about interface design? Is interface design becoming increasingly specialized for designing system components, with interaction design growing more technical for shaping flows, data models, and interactions?

- In a conversational, AI-driven scenario, what does it mean to design or express a brand? How does language change when the verbal takes precedence over the visual?

At Tangible, we’ve always had hybrid, T-shaped roles, which we’ve written about before. These roles have often been challenging for new joiners, given the broad set of skills involved.

We’ve resisted the fragmentation of roles that we’ve recently seen in the market, favouring profiles with greater breadth. We insist on areas of overlap between roles to foster collaboration and expansions into technology and business. This allows our employees to act as connectors in projects. Today, we see even greater value in this breadth.

We’re spreading theoretical and practical AI skills across every role and part of the design process. Just as designing good UX has always required a cross-functional team, designing AI-powered experiences will too. Even more so.

This is important for two reasons: first, it enables and distributes initiative and innovation internally (anyone, in any role, can identify and suggest areas for improvement with AI, introduce tools, and conduct experiments), and second, it allows us to imagine and design new experiences for our clients and leverage AI to solve design challenges, regardless of role and with minimal bottlenecks.

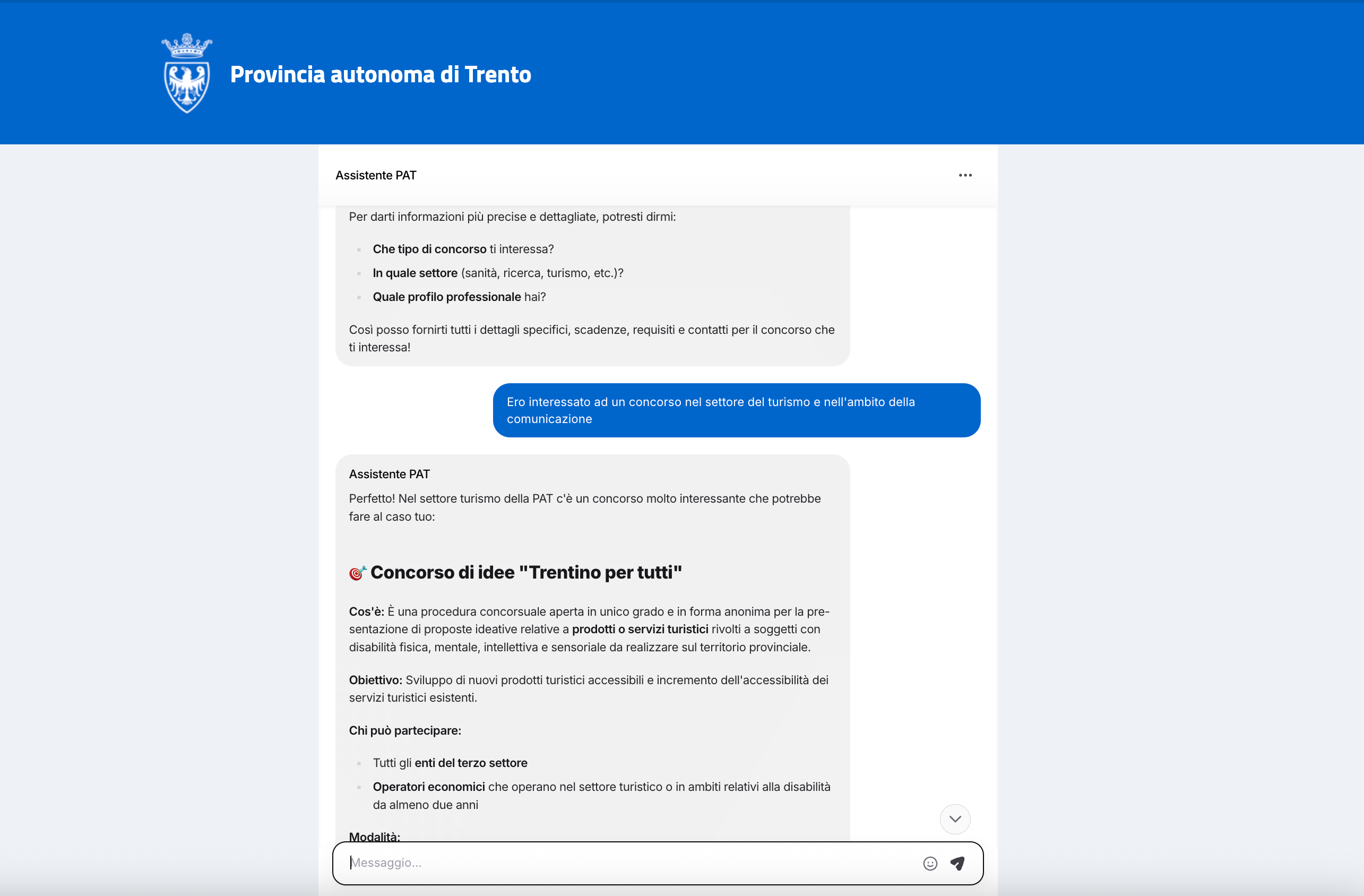

One example? For a user research project, we needed to explore people’s expectations, reactions, trust, and interactions with a chatbot that was still under development. Why not prototype the chatbot using a mix of AI tools and real content to gather more realistic feedback?

R&D and continuous innovation

For some years now, Tangible has had research and development structures operating in circles. People dedicate part of their time and goals to these structures, and colleagues contribute as needed. There is also a rotation of participants over time. We call these structures "Stacks," and they emerged from the organizational transformation work we did with Peoplerise.

Recently, our main area of research has been applying AI to design processes, building on our previous focus on DesignOps.

It’s a continuous process of research and experimentation that shares new tools, skills, and ways of working with the teams. Ultimately, it adjusts the workflow itself along the way. These small, constant improvements support the evolution of the aforementioned roles and skills - an evolution fueled by this ongoing R&D stream.

This evolution is so continuous that innovation processes must also be continuous. It's not something we can manage occasionally; it accompanies us throughout the process. Research must be followed by adoption.

We experiment with all of this directly on ourselves. We've always been a living prototype of the organization we want to become. These are also the approaches and ways of working that we recommend for our client projects.

💡 The workshop mentioned in this article was designed specifically to address the issue we wanted to tackle. We do the same thing with our clients. We combine a series of tools and facilitate ad hoc workshops for different business contexts and challenges. We've worked with corporate, retail, finance, and banking clients on exploring future scenarios, developing product/service strategies, and building action plans.

A process similar to our R&D also takes place in projects. It's called Continuous Discovery. It explores opportunities and problems, generates experiments, and validates solutions to continuously feed the operational or product development workflow.

The continuity between our internal experiments and the projects we work on strengthens our approach.

If you’d like to discuss applying these activities to your organization, you can book a conversation with us.